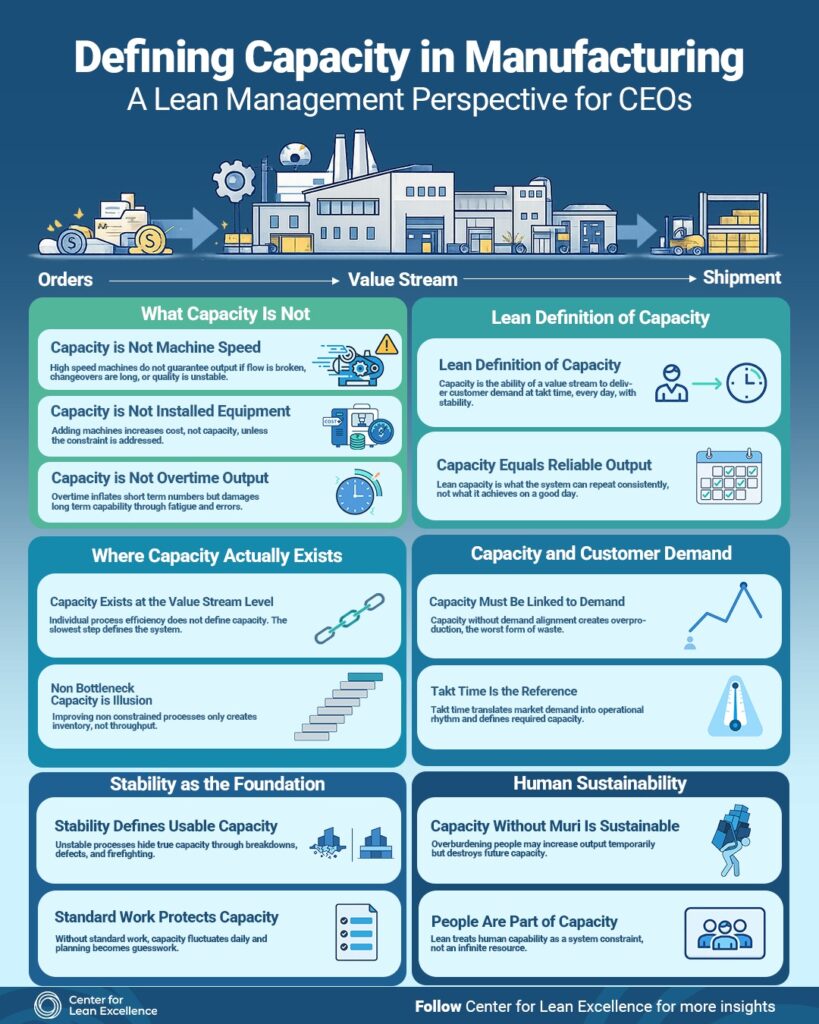

Capacity in manufacturing is often misunderstood; and that misunderstanding leads to poor investment decisions, missed delivery targets, excess overtime and hidden waste. Many leaders still define capacity based on machine speed, installed equipment or maximum output during peak performance days. From a Lean management perspective, this is not only inaccurate; it is dangerous.

True manufacturing capacity must be defined at the value stream level, linked to customer demand, grounded in stability and sustained by people-centered systems. Let’s break down what capacity really means in Lean manufacturing and what it does not.

The Flow View: From Orders to Shipment

Capacity should be evaluated across the entire flow; from incoming orders through the value stream to final shipment. A fast machine in the middle of a broken flow does not increase capacity. Instead, it often creates more inventory, more waiting, and more chaos.

Lean leaders focus on end-to-end throughput, not isolated process performance. The question is not “How fast can this machine run?” but rather:

“How reliably can we deliver customer demand every day?”

What Capacity Is Not

Many organizations measure capacity incorrectly. Lean thinking clearly separates myths from reality.

Capacity Is Not Machine Speed

High-speed equipment does not guarantee higher output. If changeovers are long, quality is unstable, or upstream supply is inconsistent, machine speed becomes irrelevant. Flow interruptions reduce real capacity far more than slow cycle times.

Capacity Is Not Installed Equipment

Buying more machines increases cost; not necessarily capacity. If the true constraint is elsewhere in the system, new equipment simply adds unused potential and capital waste.

Capacity Is Not Overtime Output

Overtime can temporarily inflate numbers but damages long-term capability through fatigue, errors, turnover and instability. Sustainable capacity cannot be built on overburden.

Lean Definition of Manufacturing Capacity

From a Lean perspective:

Capacity is the ability of a value stream to deliver customer demand at takt time; every day, with stability.

This definition shifts the focus from peak performance to repeatable performance. The best measure of capacity is not what happens on your best day, but what the system can reliably repeat under normal conditions.

Lean capacity equals reliable output, not theoretical maximum output.

Where Capacity Actually Exists

Capacity Exists at the Value Stream Level

Individual process efficiency does not define system capacity. The slowest step, the constraint; determines total throughput. Improving non-constraint steps may increase activity, but it will not increase shipped output.

Executives must map and manage the value stream, not isolated departments.

Non-Bottleneck Improvements Can Be Misleading

Improving a non-constraint process often creates more work-in-progress inventory instead of more shipments. This gives a false sense of productivity while increasing lead time and hiding problems.

Real capacity improvement comes from constraint-focused improvement.

Capacity Must Be Linked to Customer Demand

Capacity without demand alignment leads directly to overproduction; the most serious form of waste in Lean.

Demand Alignment Is Essential

If production runs ahead of demand, inventory grows and flexibility drops. Lean capacity planning always starts with real customer need, not internal utilization targets.

Takt Time Is the Reference

Takt time converts customer demand into operational rhythm. It defines how often a unit must be produced to meet demand. True capacity must be measured against takt time; not against historical averages or machine specifications.

When output matches takt time consistently, the system is properly balanced.

Stability Is the Foundation of Usable Capacity

Unstable processes destroy real capacity through breakdowns, firefighting, defects, and variability.

Stability Defines Usable Capacity

If processes frequently stop, drift, or produce defects, theoretical capacity is meaningless. Stability enables predictability; and predictability enables planning.

Standard Work Protects Capacity

Without standard work, output fluctuates daily and capacity calculations become guesswork. Standard work ensures repeatability, training consistency, and performance visibility; all required for dependable capacity.

Human Sustainability Is Part of Capacity

Lean management treats people as a system constraint; not an infinite resource.

Capacity Without Muri Is Sustainable

Overburden (muri) may raise short-term output but reduces long-term capability. Injuries, burnout, turnover, and quality loss follow overloaded systems. Sustainable capacity respects human limits.

People Are Part of the Capacity Equation

Skills, cross-training, problem-solving ability, and engagement directly affect throughput. Investing in people capability is investing in capacity.

This is a core principle taught in structured Toyota Production System training, where leaders learn how to design human-centered, high-performance production systems rather than machine-centered ones.

Why CEOs Should Care About Lean Capacity Definition

When capacity is misdefined, companies:

- Overspend on equipment

- Run excessive overtime

- Build excess inventory

- Miss customer delivery dates

- Misread performance data

When capacity is correctly defined using Lean principles, companies:

- Improve delivery reliability

- Reduce capital waste

- Increase throughput without overburden

- Align production with demand

- Build sustainable operations

Executive understanding is critical because capacity decisions are strategic not operational.

Building Capability Through Structured Learning

Understanding Lean capacity concepts requires more than theory. Leaders and managers benefit from structured Toyota Production System training programs that teach value stream thinking, takt-based planning, constraint management and stability design through real case applications.

Organizations that invest in this capability consistently outperform those that rely only on traditional capacity formulas.